An Era of High-Hanging Fruit - part 1

On the death of fresh ideas in our political conversation.

A few years ago, I found myself trying to flog patent software as a cold caller, and while brushing up on the pharmaceuticals sector, I came across a fact that over the years changed how I saw the world at present: drug discovery, and R&D across multiple sectors, is slowing down dramatically.

For decades, scientists have been spending more and more money, yet bringing fewer breakthrough drugs to market—a paradox dubbed "Eroom's Law," the inverse of Moore's Law. The numbers are striking: today's pharmaceutical companies invest billions to achieve what previously took mere millions. Why?

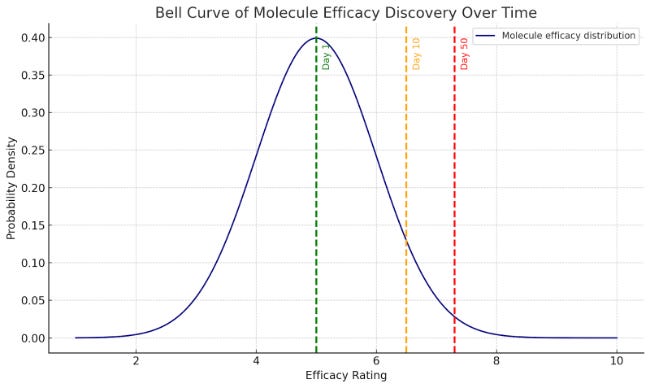

Imagine a vast reservoir of one million molecules, all potential candidates for curing Disease X. Each molecule has an efficacy rating from 1 to 10, most clustering around the middle (5 out of 10), with very few extremely weak or strong. Every day, researchers randomly test one new molecule.

On the very first day, any molecule tested instantly becomes the "best" we've seen. Statistically, that's likely around a 5.0—decent but not ground-breaking. Day two brings a 50% chance of finding something better. After ten days, the top molecule might score around 6.5. After 50 days, we've barely edged up to around 7.3. However, each new discovery faces increasingly daunting odds of surpassing what's already known. By day 100, the chance drops to just 1%. After 500 days? Just 0.2%.

This pattern of diminishing returns isn't just theoretical: it's backed by the reality of drug discovery today. Despite huge increases in research investment, the annual number of FDA-approved "new molecular entities" hasn't consistently risen in decades. In 1990, pharma spent roughly $300‑400 m per new molecule (inflation‑adjusted). By 2020 that figure is $2.1 bn. Simply put, we're working harder than ever to find fewer and fewer standout medicines.

Why does this happen? It's a statistical inevitability. The easy-to-find, effective treatments—the low-hanging fruit—are quickly discovered. Soon, we're left sifting through a sea of mediocrity, with genuine breakthroughs becoming rarer by the day. Today, it takes on average 12–15 years and $2 billion to bring a single new drug to market. Some of the slowdown is undoubtedly bureaucratic—regulatory hurdles have grown heavier. But even if approval pipelines were frictionless, the underlying maths points to a tougher hunt: the low-hanging molecules are simply rarer now.

It's Not Just Medicine—Other Fields Face the Same Challenge

This slowdown isn't unique to pharmaceuticals: similar trends have emerged across many fields over the past fifty years.

Take semiconductor technology. Between 1970 and 2000, the number of transistors on a chip doubled roughly every 18 months, boosting computing power at an incredible pace. Today, however, improvements have slowed: TSMC’s latest fab (Arizona) will cost $25 billion, versus $1 billion for a 180nm plant in 2000, and each new node requires mind-boggling engineering feats to eke out modest gains in speed or energy efficiency.

Agriculture has followed a similar curve. The Green Revolution between 1940 and 1980 led to wheat and rice yields doubling or tripling in many parts of the world. Yet, since 1990, yield growth in major crops like wheat and corn has stagnated at under 1% per year, even as R&D spending and biotech advances continue to rise. Each additional ton of grain demands disproportionately more resources, innovation, and political coordination.

Likewise, aviation—once a hotbed of massive leaps like the transition from propellers to jets—has seen only minor efficiency improvements since the 1970s, despite huge investments in lightweight materials and engine design - Pratt & Whitney’s GTF engine is 16% more fuel‑efficient than 1990’s CFM56; not trivial, but small versus the jump from piston to turbojet.

What these examples share is the same statistical inevitability seen in drug discovery. Once the initial breakthroughs have been made—the low-hanging fruit picked—we inevitably face a slowdown as we push into tougher territory.

Of course, not every field has slowed equally. Frontier areas like AI and synthetic biology are still in their early phases of discovery. But in many mature sectors the pattern of harder, slower gains is unmistakable

The Diminishing Returns of Political Innovation

The same pattern of diminishing returns appears when we examine politics. In both the UK and the USA, the twentieth century was a time of sweeping, ambitious reforms. From the 1970s through to the 1990s, governments tackled grand challenges and remade the social and economic landscape.

Crucially, it is key to note that the vast majority of the policies listed below are structural changes, rather than the state finding areas in which to spend tens of billions extra.

In the UK in the 1970s, major systemic overhauls took place, including joining the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1973, the Equal Pay Act, the Sex Discrimination Act, and the Health and Safety at Work Act. The US mirrored this ambition by establishing the Environmental Protection Agency, passing Title IX to address gender discrimination in education, and cementing landmark rulings like Roe v. Wade. These were policies that everyone knew about because they affected ordinary people’s live on a day-to-day basis.

In the 1980s, in the UK, the Conservative government privatised major industries like British Telecom and British Gas, introduced the Right to Buy scheme for council tenants, deregulated finance through the "Big Bang" reforms, and weakened the power of trade unions. In the US, the Reagan administration ushered in sweeping tax cuts, a major escalation in the "War on Drugs," and immigration reforms under the Immigration Reform and Control Act.

In the 1990s, the Maastricht Treaty integrated the UK further into the European framework, the Good Friday Agreement ending decades of conflict in Northern Ireland, there was the establishment of a national minimum wage, and independence for the Bank of England. In the US, NAFTA reshaped North American trade, and the sweeping welfare reforms under President Clinton restructured social assistance.

Even into the 2000s, governments pursued large-scale, controversial policies: in the UK, while the Iraq War, and near-doubling NHS budgets in the UK were large-spend policies, a number of structural reforms continued, such as university tuition fee reforms, the ban on indoor smoking, or the repeal of section 28 and introduction of civil partnerships.

Yet as we enter the 2010s and 2020s, the size and ambition of political projects have visibly shrunk.

Consider the last decade in the UK: what new ideas were discussed from 2015 - 2025, other than the Brexit referendum, which its detractors have decried as a disaster and its opponents generally consider to have not been taken advantage of?

For his radicalism, Corbyn’s 2019 manifesto largely revolved around either decades-old ideas (renationalisation of various industries, more worker control in private companies) or huge spending increases (estimated at £400bn for green policies, national fibre broadband, free personal care, free university tuition, free childcare). Fresh, low-spend ideas or structural changes were absent.

The 2020 Democratic nomination had a huge field of 29 major candidates. What ideas were new and didn’t cost tens of billions? Buttigieg’s plan for a permanently balanced SCOTUS passes the test, and perhaps Booker’s baby bonds would be a high-spend high-savings issue, but generally, new ideas were few and far between.

The 2024 UK general election platforms continue illustrate this change:

Labour: Its biggest pledge was a moderate tax increase, but no increases to Income Tax, NICs or VAT, and proposing the establishment of "Great British Energy."

Conservatives: Proposed the revival of the Help to Buy scheme, a continuation of the Rwanda immigration plan, and a small boost to defence spending.

Liberal Democrats: Committed to achieving net zero carbon emissions by 2045.

Green Party: Advocated for wealth taxes, rent controls, (hardly fresh ideas) and a more ambitious net zero target by 2040.

SNP: Focused on another push for Scottish independence and expanding free school meals.

While important, none of these policies match the scale of nation-redefining decisions like creating the NHS, privatising entire industries, or building comprehensive welfare states. They are modest adjustments, careful tweaks to systems already deeply entrenched.

The United States tells a similar story. In the 2020 presidential election, Donald Trump became the first major candidate in modern history to literally run without a formal campaign platform. The Republican Party simply re-endorsed its 2016 platform without amendment, signalling not just ideological rigidity, but a fundamental exhaustion of fresh political ideas.

Biden’s accomplishments as president similarly are all based on huge spending (American Rescue Plan at $1.9 trillion, the IRA at $400bn, CHIPS Act at $280bn etc), above any new ideation.

Just as in science and technology, politics seems to have picked its low-hanging fruit. Fundamental reforms—extending civil rights, establishing universal education, building welfare states, restructuring economies—have largely been achieved.

Why the Ideas Ran Out

Why has the pace of bold new ideas slowed so dramatically over the last decade? Several forces have converged to create a uniquely stagnant period.

First, the basic infrastructure of modern states is largely built. Universal education, national healthcare systems, civil rights protections, mass communication networks, welfare states, and global trade frameworks are already in place across much of the developed world. The most glaring moral and structural deficits that demanded action in the twentieth century have been addressed—at least on paper.

Second, political and economic realities have narrowed ambition. Government debts are higher, aging populations demand more from public budgets, and electorates have become more sceptical of grand promises.

Finally, bureaucratisation has raised the activation energy required for change. Legal frameworks, international agreements, media scrutiny, and entrenched interest groups make it extraordinarily difficult to overhaul existing systems. Even well-intentioned governments find themselves mired in consultations, judicial reviews, and regulatory hurdles that slow radical change to a crawl. To some extent, the caution is understandable: a mature society values consultation, checks, and environmental care. But bureaucracy not only slows bad ideas—it also smothers the good ones.

Beyond the slowdown in policy thinking, there's been a quieter collapse: the death of political vision. In past decades, leaders dared to sketch grand futures—Kennedy’s moonshot, Thatcher’s economic revolution, Blair’s mission to prioritise education. Thinking back to the 2024 election, it was hard to say what Starmer or Sunak even dreamt of for the UK’s future, beyond slightly better management.

It’s true that simpler eras allowed simpler dreams. Yet even messy complexity demands leadership willing to aim high, rather than just manage decline.

The stifling effect of bureaucracy

Today, the heart of established systems has become increasingly hostile to bold innovation. In the UK, the expansion of human resources departments has been explosive: the HR profession has grown by 42% between 2011 and 2021, compared to just 10% for the general workforce according to the CIPD's latest UK people profession update. Instead of serving merely as internal advisors, HR departments increasingly enforce complex regulatory compliance, risk aversion, and procedural rigidity—often stifling creative risk-taking within organisations.

In the US, the legal environment further discourages boldness. American businesses face an estimated 15 million civil lawsuits annually, with employment-related claims among the most common. The cost of defending against lawsuits, even spurious ones, creates a strong disincentive for businesses to experiment or innovate internally. Leaders now spend as much time managing legal risks as they do pursuing bold ideas.

Government processes have also become barriers rather than enablers. In the UK, judicial reviews—legal challenges to government decisions—have quadrupled since the 1980s. Infrastructure megaprojects have suffered enormously. HS2, originally costed at around £37 billion, ballooned to estimates over £100 billion, with lengthy delays often driven by protracted legal battles and environmental reviews.

The Lower Thames Crossing project—intended to relieve pressure on the Dartford Crossing—has been stuck in consultation and environmental review stages for over a decade, with over 60,000 pages of documentation submitted just for the environmental statement.

Similarly, new nuclear power stations face endless hurdles. The Sizewell C project, intended to strengthen the UK’s energy resilience, required an Environmental Impact Assessment that exceeded 40,000 pages, contributing to an approval timeline that stretched over twelve years before construction could even begin.

This bureaucratisation of the core leaves little space for innovation. Where once governments and companies could attempt bold reforms or experiments—even risking failure—today, any deviation from established processes invites lawsuits, regulatory penalties, activist campaigns, or internal disciplinary action.

How We Can Create Our Own Fresh Ideas

Even if the grand frontier of innovation has narrowed, it doesn’t mean we are powerless. Waiting for the next major paradigm shift doesn’t mean sitting idle. I've found three practical methods that anyone can use to come up with fresh, radical ideas even in a crowded, overregulated world.

1. Long-Term Vision

One of the most powerful ways to think differently is to start from the distant future and work backwards. Instead of asking "what small change can we make today," I try to imagine what I would want the UK to look like in 30 years: thriving cities, affordable housing, energy independence, a vibrant economy, better health outcomes. Then I work backwards: what practical steps would we have to start taking now to reach that future?

For example, I want the UK to become a high-trust society—more like the Nordics or Japan, where people feel secure, public spaces are respected, and transactions are simpler because people expect honesty. Working backwards, I ask: what drives trust?

2. Using AI as a Thinking Partner

Another tool I use is asking ChatGPT to bounce ideas around with me. It doesn't always produce perfect solutions—and that's not the point. Often the ideas it suggests don't quite work, but they force me to view problems from new angles. An imperfect answer can spark a much better one. Even half-baked suggestions sometimes shine a light on hidden assumptions I hadn't questioned. The iterative dialogue pushes me to sharpen, refine, and rethink what I thought I knew. In a world where formal bureaucracies often suppress creative brainstorming, having an AI thinking partner opens up new spaces for mental exploration.

3. Simple Problem Analysis

Finally, I look around and ask: what’s obviously going wrong? Where is frustration, decay, or decline visible in daily life? My parents complaining that NHS dental services have vanished near them is a real-world example. Instead of reinventing the wheel, I look internationally: which countries do this better, and how? The UK civil service often resists copying foreign ideas, but there's no shame in importing good solutions. Sometimes the radical idea isn't inventing something brand new—it’s simply adapting something that already works elsewhere.

Time to prove that new ideas can still be developed.

Part 2 of this essay is a list of 25 radical policy proposals — ideas that are completely absent from the UK's political conversation today.

It doesn’t take a genius to transform the country, if given a budget of tens of billions. Conversely, we appear to be blessed with politicians who manage to spend tens of billions making things worse.

The policies you’ll find following are designed with a different spirit, in that they are either low-cost, or at worst they involve spending millions to save billions over time.

But the key point is not to adopt these policies wholesale.

The real point is to change how you see our political landscape — to show that radical, transformative thinking is still possible. If you think 90% of these are ridiculous and unworkable, that’s not a concern to me: this is not a new manifesto.

This is an invitation to think differently.

I hope, as you read, you'll find yourself inspired to invent ideas of your own — and to add something new, something real, to the UK's sclerotic political conversation.

As a sample of the kind of radical ideas that we could implement to save thousands of lives and billions in the process:

Policy 1 - Legalise Kidney Sales

Legalising regulated kidney sales would allow individuals to sell a kidney under strict medical supervision, increasing supply for transplant patients.

In the UK, over 5,000 people are on the transplant waiting list, with around 1,000 dying annually while waiting. NHS England spends roughly £1.5 billion per year on dialysis services. In the United States, the cost is even starker — over $49 billion annually is spent through Medicare alone for patients with kidney failure. Legalising regulated sales could sharply reduce these spiralling costs. Iran — the only country with a regulated kidney market — has eliminated its transplant waiting list while maintaining strong ethical protections. The thought of allowing organ sales is obviously uncomfortable, but the alternative is simple: spending billions to have more deaths.

To read the full list of 25 ideas, please continue to part 2.